Tishrei is the seventh month of the Hebrew calendar that starts with Rosh-HaShana — the Hebrew New Year*. It is a 30 days month that usually occurs in September-October. One interesting feature of Tishrei is the fact that it is full of holidays: Rosh-HaShana (New Year), Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), first and last days of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles) **. All these days are rest days in Israel. Every holiday eve is also a de facto rest day in many industries (high tech included). So now we have 8 resting days that add to the usual Friday/Saturday pairs, resulting in very sparse work weeks. But that’s not all: the period between the first and the last Sukkot days are mostly considered as half working days. Also, the children are at home since all the schools and kindergartens are on vacation so we will treat those days as half working days in the following analysis.

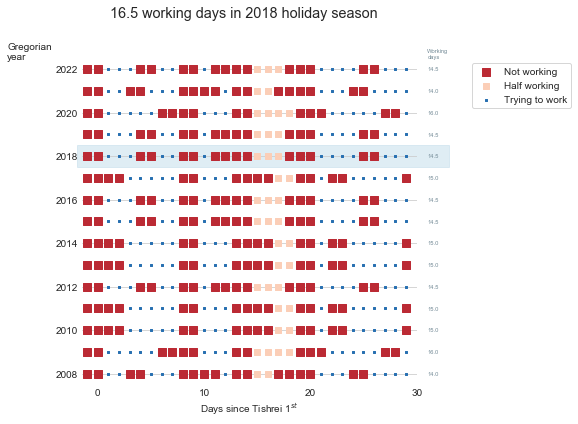

I have counted the number of business days during this 31-day period (one day before the New Year plus the entire month of Tishrei) between for a perios of several years.

Overall, this period consists of between 14 to 17 working days in a single month (31 days, mind you). This year, we only have 14 working days during the Tishrei holiday period. This is how the working/not-working time during this month looks like:

Now, having some vacation is nice, but this month is absolutely crazy. There is not a single full working week during this month. It is very similar to the constantly interrupt work day, but at a different scale.

So, next time you wonder why your Israeli colleague, customer or partner barely works during September-October, recall this post.

(*) New Year starts in the seventh’s month? I know this is confusing. That’s because we number Nissan — the month of the Exodus from Egypt as the first month.

(**)If you are an observing Jew, you should add to this list Fast of Gedalia, but we will omit it from this discussion